Ikkyo: The „living fossil” From samurai logic to the art of peace

-

January 25, 2026 -

Ferenc Németh

There is a saying every beginner learns early on the tatami: "Ikkyo issho" – meaning ikkyo takes a lifetime to master. But have you ever wondered why this is exactly the first technique? Why don't we start with a spectacular throw that would make everyone feel like an action movie hero?

This article is not just a technical description. We are doing a deep dive into the world of ikkyo (first teaching) to understand why we can look at it as a "living fossil" that preserved the feudal samurai's combat logic, while today it serves the art of peace.

Join me as we unravel the layers: from historical roots through ruthless physics to the unique, swordsmanship-based approach of Nishio Budo.

1. From „jutsu” to „do”: Historical evolution

To truly understand what we are doing with our hands during ikkyo, we must travel back to an era where the goal of combat was not yet harmony, but pure survival.

The Daito-ryu heritage: When the goal was breaking

The technical DNA of aikido originates from Daito-ryu aiki-jujutsu. In the system of Takeda Sokaku, the dreaded master, the technique we know today as ikkyo was still called ikkajo (first article). This did not mean a single elegant movement, but a complete group of techniques: a brutal catalogue of joint locks and pins.

In the pre-war era, Morihei Ueshiba also taught under this name. At that time, the goal was clearly martial in nature: dislocating the enemy's elbow or shoulder joint, painful pinning, and incapacitation dominated the practice.

Semantic shift: From ikkajo to ikkyo

When the name changed to ikkyo (一教 – first teaching), it was not merely a linguistic refinement, but a sign of a philosophical revolution. The use of the character kyo (teaching/principle) signaled: this is no longer about listing variations, but about mastering a universal fundamental principle.

Ikkyo is more than "item number 1" on an exam sheet. It is the primal principle from which all further understanding flows. If you understand ikkyo – the connection, the centerline, and the balance – then you truly understand aikido itself.

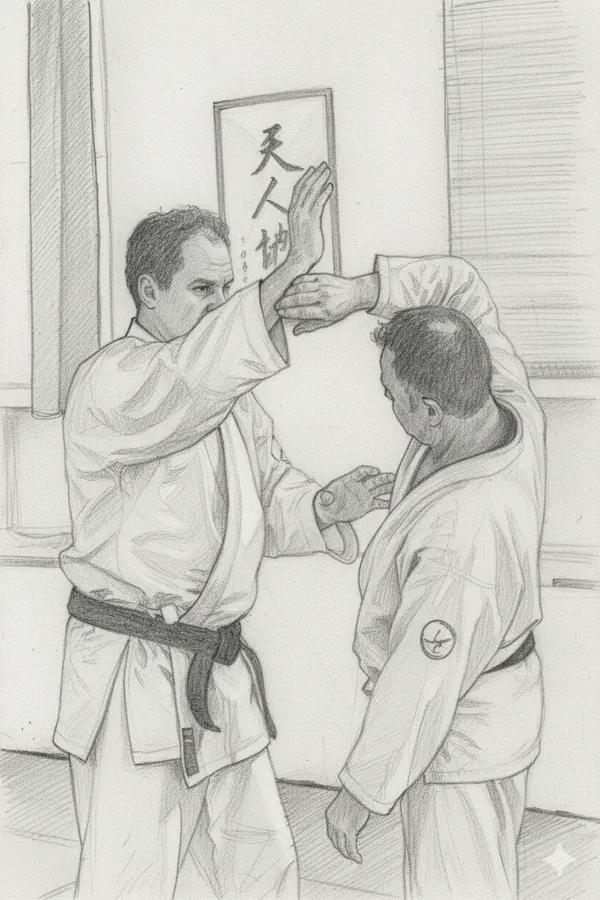

2. The anatomy of ikkyo: Why is this the "entry"?

Many beginner aikidoka feel that ikkyo is difficult, even frustrating at times. This is no accident. Ikkyo is nothing less than the key and cornerstone of the entire aikido system.

Why do we practice this so much? Because this movement teaches the fundamental off-balancing (kuzushi) without which the system collapses. Think of it as the foundation of a house: if you fail to take the uke's balance at ikkyo, the subsequent techniques – nikyo, sankyo, yonkyo, and gokyo – simply will not work. These techniques all flow from the same root; if the start is wrong, the continuation is impossible.

The mechanics of kuzushi: The spring principle

The secret of effective off-balancing is that it can never come solely from the strength of the arm or shoulder – though our instincts might dictate otherwise. The real source of power is the work of the hips and torso. Imagine your body as a spring:

- The winding (tenkan): During the introductory tenkan movement, when you create space for the connection, your body and torso "twist together." At this point, you accumulate potential energy, like a tightened spring.

- The release: The dynamic "untwisting" from this "wound-up" state is what transfers the energy to the uke's body. This rotational force is what breaks the balance, not the pushing power of your arms.

The shoulder rule: The critical checkpoint

How do you know if you are doing it correctly? There is a biomechanical golden rule that immediately shows the success or failure of the technique. Observe the partner:

The uke's shoulder must end up lower than their own wrist.

During the execution of the technique, you must control the attacker's arm so that their wrist remains high (or arcs upward) while forcing their shoulder and body downward. If the uke's shoulder slides up above the line of their wrist, the power transfer breaks instantly. In such cases, the uke regains their posture ("reorganizes themselves") and can easily step out of the technique, leaving you without power.

Universal anatomy, unique approach:

Since the structure of the human body is universal – the elbow only bends in one direction, and the

shoulder's range of motion is finite – it is natural that we encounter similar locks in jujutsu, judo, or

even law enforcement close combat.

What distinguishes aikido, however, is the spirit and dynamics of execution. While elsewhere the lock is often paired with static force or inflicting pain, the goal of aikido is to use the momentum and dynamics of the attack. We don't "force" the partner into the situation; instead, through the movement of our body and the redirection of the attack's energy, we create the moment where ikkyo happens almost by itself – using as little violence as possible.

3. Omote and ura: Two sides of the coin

Aikido techniques are divided into two main directions. These are not just spatial directions, but also denote different energy qualities, depending on how the partner reacts.

- Omote (The Surface): This is yang energy. Penetrating, decisive. We use it when the tori initiates or the uke instinctively pulls back. Its essence is a linear irimi movement that boldly cuts through the uke's centerline.

- Ura (The Backside): This is yin energy. Absorbing, spiral. We apply it when the uke pushes strongly or rushes us. The tori "disappears" from the point of conflict with a tenkan movement and uses centrifugal force to lead.

4. Attack variations and positions

Although we practice ikkyo in countless situations, the essence remains the same: dominating the centerline and breaking the structure.

Whether it's parrying strikes aimed at the head (shomenuchi/yokomenuchi), where the "sword against sword" principle applies, or static grips (katatedori/ryotedori) – the mechanics of ikkyo are universal. The key is always de-ai, catching the moment of meeting.

It is worth trying different postures: suwari-waza (kneeling work) best forces the use of hip power, while hanmi-handachi (kneeling against standing) teaches handling a disadvantaged position and directing the opponent's center of gravity radically downward.

5. Buki-waza: The sword in hand

It is often said that aikido originates from swordsmanship, but in ikkyo, this becomes tangible. The hand movement, especially the characteristic "lifting" of ikkyo, actually originates from the jodan no kamae (overhead posture) and kiri-oroshi (downward cut) movements of swordsmanship.

The term te-gatana (hand-sword) is not an empty metaphor here. You must "cut" into the uke's space as if you had a real blade in your hand. This becomes life-saving especially in defense against armed attacks (knife, sword): against a knife, a loose grip is fatal; there, control must be absolute and decisive.

6. A palette of styles: Nishio Budo and the others

While the fundamental principle of ikkyo is constant, the way of execution can vary by school.

The aikikai mainstream is characterized by fluid, large circles. Here, while the hand describes a beautiful, wide arc, the body entry is relatively direct toward the uke, leaving little room for the attacker to re-establish contact or correction. Yoshinkan prefers precise, segmented movements, while the iwama style emphasizes a solid grip.

Nishio Budo (Shoji Nishio): The dynamics of drawing the sword

Shoji Nishio sensei's approach, however, is radically different. For him, the biomechanics of the technique feed directly from the movements of iaido (the art of drawing the sword), giving a unique dynamic to the motion:

- The bait: The subtlety of the Nishio style lies in the entry. At the moment of connection, we leave a tiny bit of space for the uke to feel: "Yes, I've got it, my pressure is landing."

- The vacuum: But this is an illusion. As the uke moves into this gap, we take away the support by turning our body (tenkan), so they suddenly arrive in a vacuum.

- Geometric illusion: It feels as if our hands, kept in the centerline, are moving purely vertically (like drawing a sword), while our body travels on a beautiful arc behind the hands. This duality takes away the balance.

- The cut: The finish is not a blunt push down, but a sharp cutting movement directed toward the uke's body. This "cutting into the body" is what finally decides the conflict.

7. Towards mastery: Errors and pedagogy

Ikkyo is a ruthless mirror: it immediately shows bad habits. Here are two traps that almost everyone falls into:

- Raising the shoulders: When you strain, your shoulder involuntarily slides up to your ear. With this, you have blocked your own power. The solution: Consciously drop your shoulders and lift from your legs with an exhalation.

- Chicken wing: If your elbow points sideways, your structure will be weak. Keep the elbows down and in, in front of your body (sankaku-tai).

Nishio-style specifics:

- The over-turning trap: In the omote form, if you turn too much or turn sooner than you step, you might turn in front of the attacker, offering your back or side for a second strike.

- Wrong angle: If you stop parallel to the uke, you cannot "cut." Dominating angles and triangles is vital here.

Ukemi (The role of the attacker):

Practicing ikkyo is not a one-way street. A good uke does not fall over like a sack of potatoes. In the

Nishio style, the uke feels the intent of the cut and moves to save their own joint. This is an

active, sensitive attention.

Breathing (Kokyu):

The secret of effortless power is breathing. Try it: at the moment of "pulling out and cutting," stabilize

your torso with a sharp, short exhalation. You will feel the difference in explosiveness.

8. The path of the soul: Masakatsu Agatsu

Finally, let's ask: does ikkyo have a deeper, spiritual layer? For Morihei Ueshiba (O-Sensei), the technique was never merely a physical exercise, but *misogi*, spiritual purification.

The mystery of the „One” (Ichi):

In the name of ikkyo, "one" does not denote a serial number. In Eastern thought, everything

is born from the One. When you perform this technique, you are actually restoring Unity. If ikkyo works,

then the conflict is resolved, and harmony is restored.

Connecting heaven and earth (Ten-Chi):

Observe the movement: the hands rise toward heaven (like drawing a sword), then descend to earth, grounding

the energy. You, as the executor, are the axis between the two. This movement symbolizes the restoration of

the order of creation amidst chaos.

The goal, therefore, is not to defeat the enemy, but to achieve masakatsu agatsu: "True victory is victory over oneself." When you don't break the attacker's arm during ikkyo, but control and quiet their aggression, you have actually triumphed over your own fear and anger.

Ikkyo beyond the tatami: How to handle your "boss"?

One of aikido's greatest promises is that what you learn in the dojo can also be used in your life. But how can ikkyo be applied if you are not attacked with a sword at the grocery store? The answer lies in verbal aikido.

Imagine that your boss or a family member angrily rushes at you in an argument (this is the verbal equivalent of a shomenuchi attack). Your instinctive reaction is blocking ("That's not true!") or counter-attacking ("And you always do this!"). This is the collision.

Instead, try the principle of ikkyo:

- Entry (Irimi): Do not retreat, but do not collide either. Listen to what they have to say, look them in the eye. With this, you "enter" their space.

- Connection (Musubi): Acknowledge their feelings ("I see that you are angry about this"). With this, you have caught their "wrist."

- Leading (Kuzushi): Once there is a connection, lead the conversation toward a solution ("How could we change this?"). This is the off-balancing and the completion of the technique.

This is how an ancient samurai technique becomes a modern conflict management tool.

The Japanese name for pinning is osae (e.g., ikkyo osae). This verb does not mean "crushing" or "oppressing," but rather "keeping something in place," "controlling a situation," or "quieting down." Exactly like putting a weight on paper so the wind doesn't blow it away – stably, but not destructively.

Conclusion

Ikkyo is the microcosm of aikido. It contains everything: martial rigor, the laws of biomechanics, the elegance of swordsmanship, and spiritual aspiration. The next time you stand on the tatami and it's ikkyo's turn again, don't just see a repetition in it. See in it the opportunity to polish the connection, the balance, and the mastery over yourself.